One White Guy’s Take on “Multiculturalism” and Steampunk

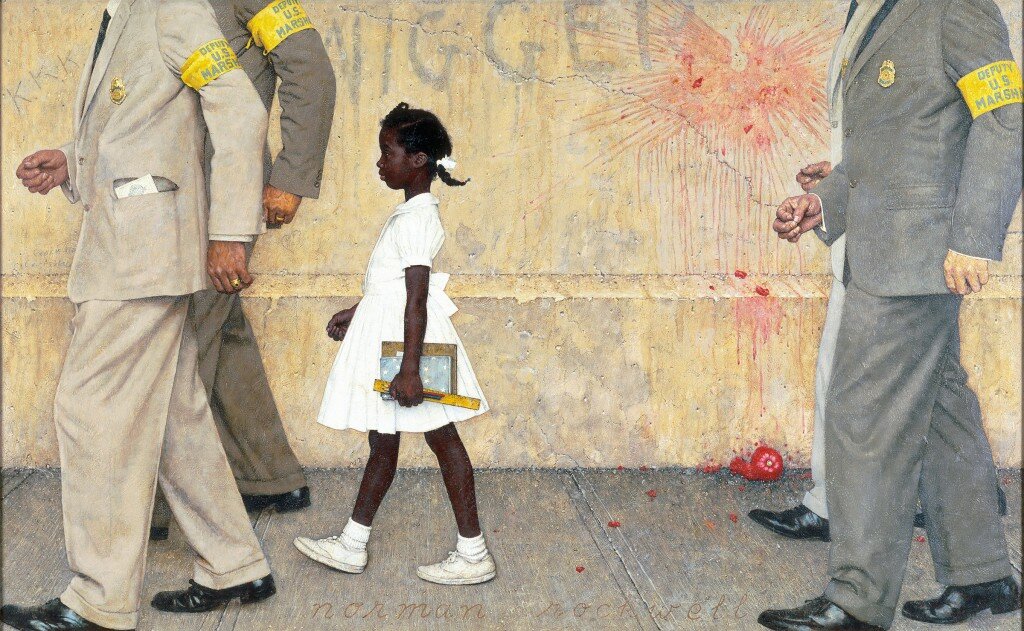

Given the sorry state of inter-cultural relations in our world it isn’t any surprise that the Steampunk community also suffers from issues of intolerance and obliviousness. In general, I think that we do better than a lot of sub-cultures at celebrating difference and embracing diversity. But we also have to police ourselves far more since so much of our culture is tangled up in nostalgia for a century in which institutionalized racism and sexism were the order of the day. Dressing up like a vampire or a Japanese pop star is one thing, but when one is wearing a costume inspired by a conquering 19th century European imperialist army one has to be extra willing to address the concerns of people who still feel oppressed by the legacies of that imperialist culture.

In many minds the pith helmet remains a symbol of oppression – a garment worn by the armed forces and administrators of conquerors. But for most steampunks it is nothing more than a symbol of anachronism. Who is right? (via http://www.flickr.com/photos/29383501@N08/7290524760/in/pool-pith_helmets)

As the moderator of a large Steampunk community, I have often been criticized for having too thin a skin, for “having the super power of being offended by everything,” for pointing out when any given bit of media might be taken as offensive. This essay is meant as the defense of that position: as an argument for why our community (and probably the larger world) would be better off if we made a more conspicuous effort to understand how and why something might be perceived as hurtful, even if it doesn’t particularly bother us – even if we like it.

At the outset let me acknowledge that I am an upper middle class white heterosexual protestant male doctor born in the United State. In short, I am child of privilege who has never been made to feel unworthy because of the color of my skin, what god I worship, the shape of my genitalia, or the choice of what I do with that genitalia. I have never gone hungry except by choice; I have never been afraid that I was going to be shot because a vigilante assumed I was a drug dealer; I have never been assaulted because someone thought I was dressed in a way that “asked for it.” That is not to say that my life has been without challenges – I have worked very hard for my successes, but I appreciate how solidly the deck has always been stacked in my favor. Mommy and Daddy didn’t buy my current position, but I realize that I wouldn’t have been worrying about my choice of Ivy League college if I’d instead been working two after school jobs for food.

The fact that I could be a poster child for some Northern European Racial League would seem to make me a terrible person to voice any opinion about cultural diversity. But there’s a certain “Only Nixon could go to China” process in play. People of color (or in some other arbitrarily defined biosociocultural minority) already realize the importance of tolerance and diversity. Conversely, someone who doesn’t appreciate the value of a minority opinion is hardly going to be swayed by advocacy from that minority. My hope is that here, speaking as someone without any particular social grievance to air, I can connect with those who wouldn’t be willing or able to hear me if I were female/gay/black/etc.

Let me also say that I’m not talking about social policy here – just personal behavior. Much of the backlash against the celebration of diversity has come from well-intentioned but often ham-handed political movements that have only served to provoke people who hate being told what to do. I am not telling you or anyone else what to do. I am also thankfully not in charge of any governmental policy. I am only offering a few ideas that I personally try to keep in mind to guide my behavior. I hope that some of them might speak to you too. If they do, great. If not, well, that’s okay too.

American illustrator J.C. Leyendecker, with his Saturday Evening Post covers and innumerable fashion illustrations helped shape our conceptions of fashion and sport – helped determine what it means to be a virile straight red-blooded American man. He was also (almost certainly) a homosexual. Rarely are the boxes we create to categorize people as legitimate as we believe they are.

Finally, I apologize in advance for my language and my tone. I am going to play fast and loose with words like culture and race and society. I am not writing this for social historians or cultural anthropologists – I hope they don’t need to hear any of this; and if you are going to tear apart my arguments because of my lack of taxonomic rigor you have profoundly missed the point anyway. Likewise, I suffer from intractable optimism about human nature and have been known to lapse into speaking like an after school special. I know that cynicism and bitterness are way cooler – but sometimes I wish that more people tried to live up to the messages at the end of GI Joe (be nice to minorities, don’t light things on fire, etc.) instead of acting like the typical snarky asocial jerks on the internet. As a result, this reads like I believe people are good and want to be better, and it makes clear that II don’t mind a little bit of cheesiness and maybe even a tiny bit of patronization.

Without further ado – here is my multi-part guide to successful inter-cultural Steampunk relations:

1. Instead of telling someone they shouldn’t be offended, try to understand why they are.

I think that most people are well-intentioned and absolutely don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings. However, we spend all of our time living in our own brains and thus have a hard time understanding that other people don’t necessarily see and understand the world the same way that we do. Since we know that we didn’t intend to do anything hurtful, since our behavior wouldn’t be offensive to us, and since the things we like don’t offend us – we assume that anyone who is hurt or offended simply doesn’t understand. We also understandably get a little defensive if someone challenges us or something we like – particularly if they do so aggressively by calling us racist.

The temptation is to make it an argument – to prove that you’re right and that someone else is wrong. Ultimately, though, it doesn’t matter who is right. No one cares. Well, maybe someone on the internet who would “like” your argument more cares, but that person probably also just “liked” a picture of a cat in goggles. That goes for both sides of the argument. The point is not to “win” and demonstrate that someone’s outfit/movie/accent/whatever is racist any more than it is to demonstrate that someone offended by it is a thin-skinned idiot. Anyone who has ever had an argument where the goal was to “win” knows that the absolute best you can hope for is that one party gets so offended that they walk away.

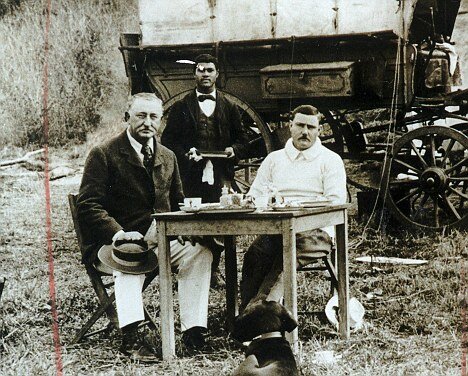

I took this image of imperialist extraordinaire Cecil Rhodes (with African servant) from a (conservative) British newspaper that was making a troubling argument for a return to uplifting imperialist ideals. Steampunk is not going to solve the question of whether Rhodes and those like him were racist theives or whether they were noble heroes – but we have an opportunity to understand why some members of our community strongly believe in one or the other of those points of view.

The solution, however, isn’t to avoid talking – it’s to keep the conversation civil and to try to be understanding. When someone is offended by something and someone else isn’t, it means that there is an opportunity for learning on both sides. If someone is offended, it’s for a reason. Maybe it reminds them of generations of colonial exploitation. Maybe they see the theft of cultural iconography they view as proprietary. And maybe they are just a thin-skinned idiot. Likewise, if someone thinks they are justified it’s for a reason too. Maybe they are trying to make commentary on the aforementioned colonialism. Maybe they are trying to celebrate rather than appropriate a culture not their own. And maybe they are just racist bastards.

None of this means that you have to agree with someone’s objections or with someone’s justifications. You can dress and act and enjoy yourself any way that you want if you’re willing to accept the consequences (including potentially hurting someone else’s feelings). Likewise, you can be offended by anything that you want and reject any efforts at conciliation short of abject surrender. But either way you’re doing yourself a disservice if you don’t try, at least for a while, to inhabit the experiences of the person on the other side of the debate.

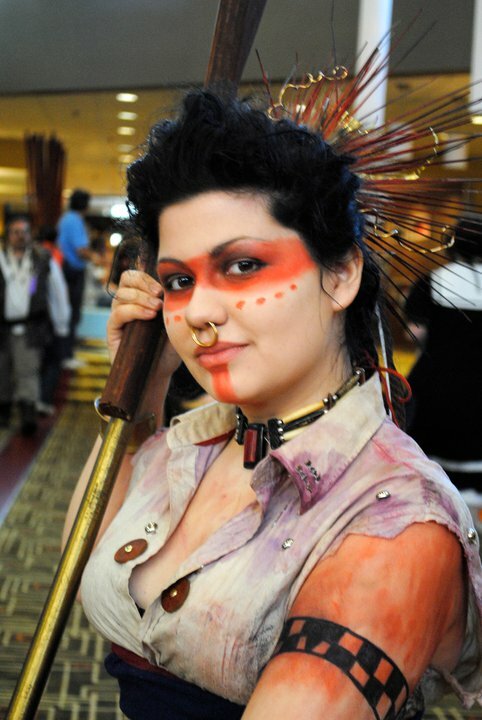

Such conflicts are certainly not limited to issues of ethnicity. Are representations of women (albeit cyborg ones) like this empowering representations of women taking charge of their sexuality? Are they harmless eye candy? Do they demean and objectify?

2. Understand that there are a lot of toxic ideas from the nineteenth century (and before, and after) whose legacies we are still living with. Steampunk is an opportunity to address them, not celebrate them.

Escapist fun is a wonderful thing. We all can appreciate the humor in putting on a pith helmet and joking about tea. But two of the most defining elements of the nineteenth century were slavery and imperialism. Racism and sexism became (more) institutionalized during the period most people look to as the inspiration for Steampunk. Foundations were laid for genocidal wars. Etc. Enjoying oneself is one thing, but it is incumbent upon us to remember that those pith helmets were worn by colonial armies that murdered and enslaved indigenous peoples to produce, amongst other things, tea.

I’m sure not everyone will agree with me on this, but I think that it is possible to acknowledge cultural “guilt” and to come to terms with it without accepting “blame.” I think that one can say “I’m sorry,” without embracing self-loathing. I think it is liberating to be willing to say that I regret the role the culture to which I am an inheritor played in the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of millions of Africans. It is in pretending that there is nothing to be sorry for that one develops ugly neuroses – just like an adult who never acknowledges childhood abuse. Steampunk gives us in the West a wonderful opportunity to concede that our sociopolitical dominance was not founded on cheerful Thanksgiving dinners with Indians or upon the fair exchange of goods with Africans. In my opinion our escapist fun will be richer for a moment spent considering what it is we’re escaping from.

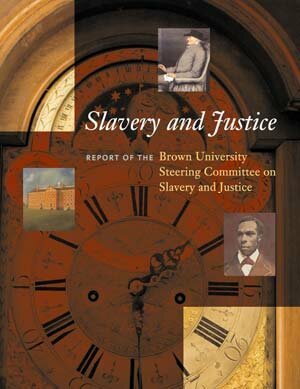

My undergraduate college, Brown, recently completed a mammoth effort to assess the extent to which profits from slavery helped fund its early years – and to determine the best means of acknowledging its resultant culpability in that abominable institution. I have never been so proud of any organization I’m associated with. The resulting report is worth reading for anyone interested in topics of cultural justice. http://brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/

There is also a practical issue here – namely, as much as we may love our sub-culture, we live in a larger world. If you dress up like an Imperial German airship pirate and speak like a character from Hogan’s Heroes, to everyone else you just look like a Nazi. Again, that can be a great opportunity to teach people what Steampunk is all about . . . or it can be a chance to make us all look like insensitive jerks.

This image was taken at some convention of some probably entirely innocent cosplayers dressing up like a fictive pre-WWI airship crew. However, whatever their intention, they end up looking like Nazis. As a general rule, one wants to think long and hard before doing anything that is going to cause you to be mistaken for a Nazi. (Although, see below.)

3. You don’t have to be a saint, but that doesn’t mean that sin is a good idea.

We’ve all laughed at racist jokes. We’ve all judged a person because of her clothes/body habitus. We’re all flawed human beings who’ve gotten carried away in a moment and said or done something that made us cringe the next day. That’s okay. It doesn’t mean we’re bad people. This isn’t a binary dichotomy. We don’t have to be either Gandhi or Hitler.

But that’s not the same as being unwilling to admit that you screwed up. The problem is when we treat someone badly because they have large breasts/dark skin/epicanthic folds/etc. and then, unwilling to admit that we made a mistake, we argue that there was nothing wrong with the behavior.

There is.

There is something wrong with doing racist/sexist/homophobic/etc. things. There is something wrong with treating anyone as a person second, and as a black/gay/woman first.

But we still do it. We still do it because we are all in the process of learning and getting better and dealing with our own baggage. Each one of those failures is an opportunity to better understand ourselves – or a chance to pretend that we’re perfect and reinforce behaviors that make both ourselves and others unhappy.

Okay, this is a bit of a graphical stretch, but a picture of a Steampunk Pope offering free gropes seemed unnecessarily provocative (see above re: trying not to be offensive). So . . . Yoda. Sadly, real people are usually less saintly than syntactically challenged Jedi muppets.

At the end of the day, no one can expect anyone else to be perfect. All anyone can ask is that you try. If I sometimes seem like I’m bending over backwards on Steampunk Facebook, it’s for that reason. When I address a hundred thousand people I will inevitably offend someone. But I’m trying.

It never hurts to let people know that this is hard and that you’re trying.

4. Culture is a dynamic and interactive creature that no one person or group owns, even in part.

I believe that we all benefit from the free exchange of ideas, from the resultant creation of novel hybrids, and from the dissemination of truly original concepts.

A much younger (and very atypically sunburnt) Coxcomb at an archaeological dig in Petra wearing traditional Bedouin dress that I’d purchased from a Jordanian teenager wearing a Titanic t-shirt. Am I a cultural imperialist? A respectful admirer of a different way of life? Or just a guy in a silly hat?

I know that I’m going to upset some people with this as cultural appropriation is an understandably touchy subject in inter-cultural relations. However, no matter what your free trade coffee house tells you, all exchange is asymmetric and the only culture that isn’t founded upon exchange is the kind that has been buried in the ground for a thousand years.

It is one thing to try to be respectful – to consider whether you really want to make a semi-pornographic music video dressed as the Virgin Mary or to dress as a Steampunk geisha while speaking like a B-movie Vietnamese prostitute. It is something else to consider assorted cultural material as so sacrosanct that it can’t be reinterpreted or applied in novel ways. It is just as insulting as overtly slighting another culture to act as if a “lesser” partner is so weak that they have to be protected from the more “dominant” one.

In other words, all cultural exchange is always bi-directional (if necessarily asymmetrically so).

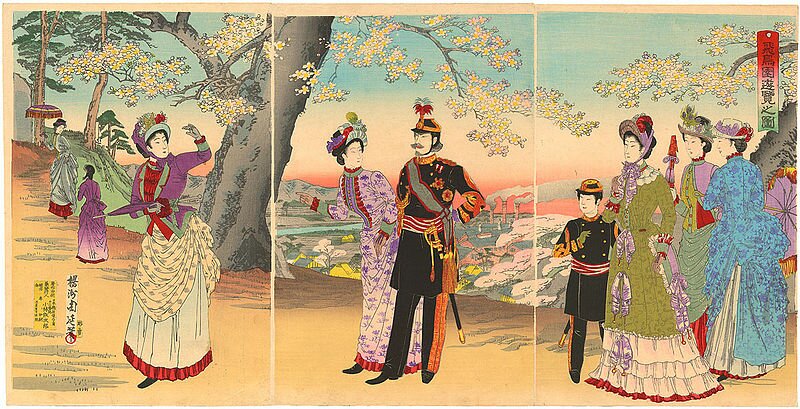

I believe (and it’s a belief, not necessarily a truth) that “culture” exists to be “stolen,” and that one of the greatest things about cross-cultural communication is the way that different people reinterpret what they encounter elsewhere. The Japanese people depicted here aren’t “stealing” Western dress any more than a European woman in a sari or a kimino is stealing something – the very act of exchange allows for the potential creation of something new and wonderful. Which isn’t to say that someone upset about seeing iconography they perceive as “theirs” used in a non-traditional way is wrong . . . just that they’d probably be happier if they could see “appropriation” as having less to do with the origin of the material and more to do with the creative (and sometimes exploitative) impulse of the appropriator.

There are a series of famous paintings of Japanese elites in the late nineteenth century dressed in contemporary Western garb. Were they being oppressed and their culture crushed? Were they stealing the culture of the Westerners? Both. And neither. Nothing has changed – except that cultural signifiers spread globally with infinitely more speed and are disconnected from any originator even more rapidly.

There is a related danger here in reifying historical cultural identity and equating that historical culture with entities in the contemporary world. It is tempting to create historical archetypes – e.g., The Native American – and demand their preservation into the present. This fails to acknowledge the dynamism of people and the fact that, for better or worse, we are all (and have been since the first Cro-Magnon raped a Neanderthal) the children of a fractured world. What is the cultural legacy of the “Chinese” food we eat in American shopping malls? Of the “Latin” mass practiced in Columbia? Of the designer clothing inspired by a museum exhibit on African tribal wear sketched out by London-born designers working in New York and assembled in Asian sweat shops to enrich investors from all over the world?

I do not for a second wish to undermine the status of the privileged viewer who feels a particular genetic/historic kinship with given cultural objects. It is deeply unfortunate that just as colonial armies stole lands and labor and dignity, contemporary information exchange would seem to steal the very identity of people who identify with an oppressed people. But the alternative is perhaps even more toxic – to pretend that there are pure cultural units that must be respected, to argue that white people must wear white people clothes and black people black people clothes and yellow people yellow people clothes.

The Steampunk blogger, Miss Kagadashi, explored her own Native American cultural heritage in an outfit that won praise as well as approbation. She was chastised both for somehow undermining a “pure” cultural representation and (by people who didn’t know her ethnic background) for dressing up in the clothes of another ethnic group. This kind of thinking illustrates the perils of demanding cultural compartmentalization. Do we want to live in a world where one must have a blood test before being allowed to wear particular clothes? (http://thesteamerstrunk.blogspot.com/2011/03/my-nativepunk-and-some-anachrocon.html)

Again, appreciating and trying to understand the feelings of someone affronted is one thing, accepting that all culture must be parceled out into artificial boxes is something else entirely. We must celebrate the cultural legacy of the past without getting trapped by historical stereotypes that reify a past that never was and that confine the real people of today (sometimes by their own choice) in a mythological prison of what we imagine the Jews/Thais/women/whatever of 50/100/1000 years ago to have been.

5. Punk it.

While I adamantly refuse to advance a definition of Steampunk, and I think it’s ridiculous to demand that its name be the primary determinant of what it is . . . I do believe that its origins in socially rebellious literature and the ongoing fringe status of the community mean that it is well suited to cultural critique. In fact, for me, one of the most appealing aspects of Steampunk is its (perhaps unique) position to expose the evils of, and to re-evaluate the opportunities at the root of, twenty-first century civilization. Who better than Steampunks, steeped as we are in the culture of the period during which Modernity was born, to assess the weaknesses and strengths of that Modernity?

“And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic Mills?”- William Blake

Moreover, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, the whimsical ahistoricity of our culture makes it possible for us to address relevant sociopolitical issues of today in ways that fly under the radar of people who would otherwise be unwilling to question their beliefs. There are plenty of people who would defend the rights and privileges of contemporary bankers, but who would be happy within a Steampunk setting to challenge those same prerogatives held by old-timey robber barons. My point is just that Steampunk, like much science fiction parable, makes it possible to critique the present obliquely.

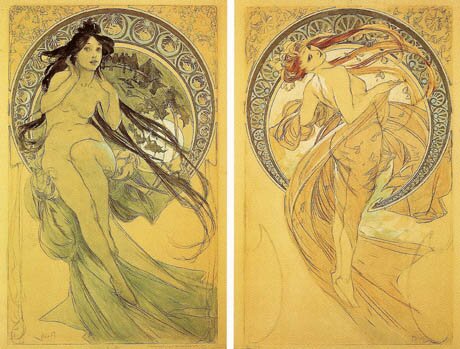

Steampunks are not the first not the last batch of creative types to struggle with the realities of contemporary industrial life. From poets (I quoted Blake above) to artists (here is Mucha looking to organic forms to rebel against a manufactured world) the effort to restore humanity to an inhuman world is ongoing.

This absolutely goes for inter-cultural relations as well . . . although one is obviously treading on dangerous ground and any effort to satirize requires the satirist to be willing to engage his or her audience and to tolerate the fact that (a) people won’t necessarily get it and (b) even if they do it might still offend them. Likewise, there is a danger of falling into the trap of “making fun of racist jokes” becoming just an excuse to tell racist jokes. There is no right answer and for every brilliant critique that forces people to re-examine their own hidden biases there is going to be an episode in which Ted Danson wears blackface.

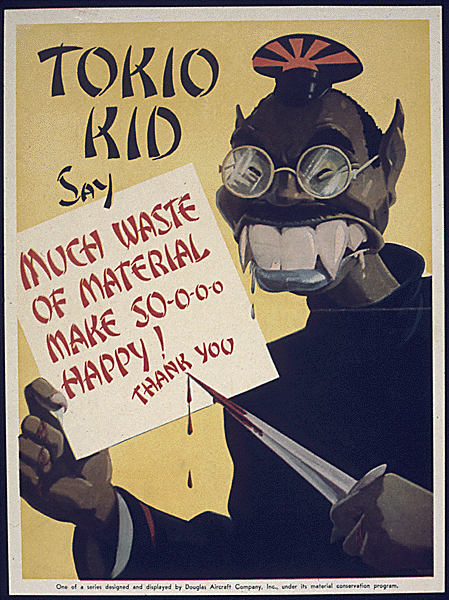

In my own experience this works best when dealing with one’s own cultural legacies of injustice. I have read about the rampant racism of Japanese Imperial culture that found its ultimate wartime expression in brutal reigns of systematized murder in places like Nanking. But I don’t feel particularly comfortable passing judgment – I come from a nation that mobilized its resources to fight Japanese injustice by interning its own citizens of Japanese descent and characterizing its enemies as inhuman “Japs.”

While I think almost all people are fundamentally good, I also believe that all people and all cultures have the capacity for profound evil. There is no question that ethnic groups other than mine have done horrible things and are guilty of plenty of crimes . . . but until I have fully come to terms with the stains on my own heritage (like this anti-Japanese WWII poster), I can leave that critique to others.

In contrast, the legacies of racism, economic exploitation, and occasional attempted genocide inflicted by Americans and by Europeans upon much of the rest of the world are something that I can very much personally understand and take ownership of. They are legacies that we still live with and ones that, as a privileged white guy, I would be remiss in failing to acknowledge as some of the reasons that I am typing this in my luxurious air-conditioned study on an expensive computer while someone as smart and as driven as me living in parts of sub-Saharan Africa is lucky to have the bare essentials for survival. One of the things that draws me to Steampunk is its ability to help me come to psychological terms with those disparities – it is a means of forcing me to look history in the eye, and maybe to draw a few eyes with me.

“If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, –

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.”- Wilfred Owen

By way of specific example, many of the costume designs for Parliament & Wake were military themed – not so much because it is a cool look as because I remain frustrated by the terrifying resource allocation human civilization continues to put toward destroying itself. But it was also to help me personally understand and take ownership of the toxic racist history that helped put me where I am now. Several of the jackets that I wear as psychological hairshirts are custom cut to the patterns worn by British, American, and German soldiers during WWI (and which are easily mistaken for those worn in WWII). I altered the colors and none of them are adorned with any of the iconography of the nations for which they were actual uniforms to avoid explicitly disrespecting the people who fought for the causes they represented. But I took it a step further. I wanted an excuse to engage with everyone who looked at the jacket and thought what great lines it had, for everyone who put on the uniform of a 19th century Imperial power without realizing that the ideology it supported wasn’t so different from that of the more brutal regimes of the mid twentieth century. By hand I copied out passages from books like “Night” and “The Origins of Totalitarianism” onto linen and then affixed them to the jackets. While they routinely get mistaken for Warhammer purity seals – they also function like flypaper as they draw people in who want to know what they say . . . and then we end up talking about race and power and all the things that make Steampunk important and relevant.

Of course, there are also plenty of people who get it exactly wrong and think that I’m just dressing up like a Nazi – it goes with the territory. That’s the risk you take when you “punk” painful history; but I still believe that it would be a waste of Steampunk not to try to use it to understand and to challenge historical assumptions about our world.

A reproduction British WWI jacket left over from my Parliament & Wake days. The back of this one is decorated with the poetry of WWI veterans (like that of Owen mentioned above). The effort, not always successful, is to force both myself and anyone who sees me to engage with the harsh discordance between the happy pageantry of militarism and the cold reality of the price of violence.

6. Remember that some people really are just jerks. But they still have something to teach.

It takes a lot of effort before I fall back on this conclusion, but it’s worth always keeping in my back pocket. There are people who are unable or unwilling to see anything but their own point of view; and there are people who just really get off on being unpleasant.

The thing to remember is that you don’t have to fix everyone’s issues. You also don’t even have to engage with them (and there are times when you really shouldn’t). But you can still learn from them. If someone is a racist/sexist/homophobic bastard (be they white or black, gentile or Jew, gay woman or straight man) they are that way for a reason. If your best efforts to be conciliatory are met with aggression and outrage, there is a reason for it. Maybe that reason is you – and it’s fair to check that first. Are you REALLY trying to be conciliatory and find a common ground? But it also might be them.

Churchill offered the inspirational wisdom to “Never give in . . . never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy.” In describing the colonization of Africa and the genocide of Native Americans, he also said this: “I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.” Food for thought.

Maybe it’s something as clichéd as the fact that they aren’t comfortable with their own sexuality. Maybe it’s the “reverse racism” inspired by a minority rebelling against the dominant racist paradigm so hard that they end up being unable to see when someone from that paradigm really is reaching out to them. Maybe it’s someone who was hurt so badly that they just won’t ever be able to see a person of a particular race or gender as anything other than a threat.

The list goes on and on but it is critical that you recognize when to give up in a particular situation, but also that you refuse to take that as an excuse to give up altogether. Every failure to successfully engage with someone is a lesson on how to succeed next time.

7. Fight it.

I like clean lines. That means that it takes a lot to get me to clutter my fridge door. At the moment there is just one thing posted there – an editorial from Esquire that I happened to read during one of the darkest days of my life. It’s entitled “Fight It” and, in short, argues that it is easy to fall into the trap of cynicism, bitterness, and judgment. It is both cool and simple to see the world as a divided place populated by a bunch of scary Others, none of whom has as good a handle on things as you do.

Most of the horrible things that people do ultimately come down to fear. The best weapon to fight fear is understanding. If we want to live in a better world we must try to understand our own fear and the fears of others. Steampunk is a fantastic tool for examining the historic roots of our own cultural fears.

I believe that we can do better than that. I believe that we all have more in common than not.

We are not going to get it right all the time, or even most of the time. I am sure that with this one essay I have offended plenty of people who are going to email me rants about what a horrible and/or moronic person I am. I’m okay with that. I’m happy to be wrong, to learn through letting other people be right.

I don’t think it’s about being right.

I think it’s about discovering ways to fight the divisions and learning to get along and respect one another. Ultimately I’d rather be wrong and have us see each other as people all traveling in the same boat; than to be right and alone.

It’s not a particularly sophisticated philosophy, but it’s been hard won, and it’s the best I can offer – for Steampunk, and for life in general.

Further Reading:

There are many other voices with things to say on this topic. The following blogs are three great places to start:

Beyond Victoriana

Multiculturalism for Steampunk

Silver Goggles

Wonderful article. Thank you so much.

I entered the world of steampunk barely a year ago. I chose to be a Steampunk Pinkerton Time Traveling Detective. I’m black and I have to explain everything about my costume and me. From what the Pinkerton National Detective Agency was, to steampunk in general and why, as a black male, I was dressed up in a genre of fantasy that centers largely around the 1800′s – not one of the shining centuries in the realm of racial harmony. Well, along with explaining the Pinkerton’s, I get to throw some [black] history in the mix and while I don’t like to play race cards – it is surprising to some that an organization as renowned as the Pinkerton’s would have afro-american working in prominent positions as detectives and secret agents. I always thought just the time-traveling steampunk part would be the most bizarre thing I’d have to explain but most people just kind of gloss over that as all I have to do is say, “Take the films, Timecop and Wild Wild West and smash them together.” Subtracting the Van Dam fighting skill of course. I’m not the most manueverable guy around. When people are still scratching their heads, I just say, I picked something that plausibly fit with history and the theme of steampunk and my race had nothing to do with it. I just love Pinkerton’s and Steampunk.

Thanks for your article.

I have been in love with Strapping for the last 7 years! I am a Cuban female and I can tell you I too get odd looks. I am trying my hand at writing the genre with a multicultural twist. The beauty of Strapping is the fantasy part. Thank you so much for shedding light on a dark subject.

I meant Steampunk!

Way to relieve yourself over someone’s hobby. I am sick of the overly-sensitive saying, essentially, that because bad things have happened, no good things can be celebrated.

Seriously, are you taking the pith?

I nodded along through most of the points in this essay. I think you did a great job of treading the thin line between the racists/sexists/ists on one side and the bitter reactionaries on the other. I doubt you’ll reach someone who really is a hardcore -ist, but you’ll speak to the mostly well-meaning people who have gotten turned off by the strident language and yelling further left of the spectrum.

Interesting that you link Silver Goggles at the bottom. I just found her blog yesterday and am still going through her posts, but so far she’s really turned *me* off – even when technically I agree with her! Whereas your essay, I felt, turned off the condescending language and will do a better job of drawing in people who would be instinctively defensive otherwise.

I was a big consumer of the cyberpunk genre but as the descendent colonized people I never got into steam punk. Beyond watching a few animes, I was not interested in the era and never ever finished Neal Stephenson’s Diamond Age. Your well thought out commentary can be applied to any sci fi/fantasy community and I will keep it bookmarked for the next time some oaf tells me I am to sensitive.

Is there such a thing as too much historical concern? In the realm of Steampunk, i’d have to say yes. In a way, human history consists of things learned by the mistakes in trying to make something else. There’s no room for anything but mourning, regrets and such fun things if you look at history with those eyes. I do not condone slavery, but i do listen to blues. I drive, even though people are killed in traffic every day. I have a bow and enjoy archery, in spite of it being a monument over the massacres of all kinds of indigenous peoples due to their inferior firepower. I do occasionally go to church, in spite of pretty much its entire history.

We’re not glorifying the atrocities committed.

We are glorifying the adventure and the adventurers, and we all wish that they had been bloodless and respectful. They weren’t, but they are in the past. What’s the point of remembering the past if all we’re supposed to do with it is feel bad?

Ease off. Steampunk is supposed to be an alternative to real history. Let’s make that alternative atrocity-free. All it takes is imagination.